|

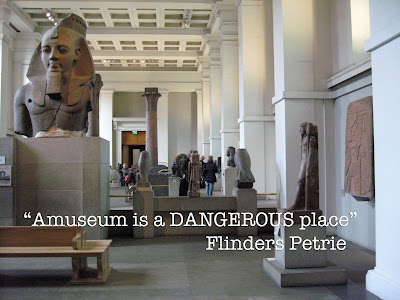

| The British Museum |

‘A MUSEUM

is a dangerous place.’

Sir

Flinders Petrie, pioneer British Egyptologist, first said those words, but

today Anson Hunter was thinking them.

A man had

followed him to the British Museum.

Who was

he?

Petrie

had been thinking about another kind of danger when he’d made his famous remark

about the dangers of museums. The founder of modern scientific Egyptology had

been alluding to the manner in which the early Cairo museum had dealt with a

royal mummy fragment found at Abydos, a single, bandaged arm, covered in

jewels, the only remains of First Dynasty king Zer.

The

curators took the jewels and tossed the arm way, the earliest royal mummy

remains ever to come to light. It was a mummy horror story to eclipse any

devised by the most febrile imagination, Anson had always thought, but right at

that moment his mind was on the other worry.

Anson

went up the steps and between the Ionic-style columns into the building. He

passed through a crowded reception hall to arrive in the Great Court beyond.

Above the

court, a tessellated glass and steel roof spread out overhead like a vast,

glowing net, catching clouds, blue sky and a spirit of illumination, while the

round, central building swelled like an ivory tower of learning. He crossed the

clean bright space before heading left to the door of the Egyptian section.

Inside

the dimmer light of the hall, a group of school children crowded around the

Rosetta Stone in its glass display case. Two little black girls peered inside,

their heads close together as they examined the stone, their hair braided in

cornrows. An African look, he thought. It linked his thoughts to Africa’s

greatest river, the Nile, and to Egypt’s irrigated fields that bounded it and

made Egypt the breadbasket of the ancient world.

He made

for the sculpture gallery.

Egypt,

both divinely monumental and naturalistic, surrounded him. Two statues of

Pharaoh Amenhotep III, powerfully formed in dark granodiorite, flanked the

entranceway to a hall, granting admittance, and inside, as stone slid by, other

familiar sights came into view, a red granite lion with charmingly crossed

forepaws, and further on, the statue of the Chief Steward Senenmut tenderly

holding the daughter of Queen Hatshepsut, the little princess Neferure, on his

lap - the child wrapped within his cloak and her face peeping out - then a

soaring, crowned head of Pharaoh Amenhotep in the background. And people

everywhere, creating a sound of buzzing like voices in a cathedral at prayer

time.

But he

barely saw or heard them. He paused at a figure standing on a pedestal near a

wall on the right hand side, almost overshadowed by a colossal granite torso of

Rameses the Great in the centre of the hall.

Khaemwaset,

the priest-prince and magician.

Anson

confronted the figure. The sculpture depicted the prince in a pleated kilt,

stepping forward while holding a pair of emblematic staves at his sides. The

conglomerate stone must have presented a technical challenge to the sculptor as

it was shot through with multi-coloured pebbles. It made Khaemwaset look as if

galaxies were exploding out of his chest.

A museum

label said:

Red

breccia standing figure... one of the favourite sons of Rameses II, the

legendary Khaemwese…

The label

used a variant spelling of the name Khaemwaset.

He looked

up at the face. Intelligent, sensitive features, faintly saddened. An air as

haunted as the face of the sphinx.

Anson

silently interrogated the statue.

Open up,

Khaemwaset. As one renegade to another, what do you really know? As a seeker of

forbidden power, did you open the sanctuary of Hathor, provoking fiery

destruction, plagues and pestilence on your father Rameses and his kingdom?

Legend tells that you found the magical Book of Thoth, so why not the disc of

Ra, too?

(Excerpt from Hathor's Holocaust)

|

| Amazon Kindle and paperback, 2nd book in the Anson Hunter series |